The EMS Guide To Infantile Spasms

- Hanna Thompson

- Jun 5, 2025

- 8 min read

You are called to a residence for a 6-month-old male who, according to the mother, has been having seizure activity. She tells you that the activity has been happening intermittently for the last week and has worsened. She also tells you that the baby has been lethargic for the previous month, hasn’t been interactive, and is sleeping more than usual. She tells you that she had taken him to the ER when this happened the first time, and they couldn’t find anything wrong with him. She also states that she took him to the local clinic and was informed that he was “normal”. When you ask the mother what the seizure activity looks like, she tells you her son will bend his arms and legs and roll his head and eyes back. She also states that the activity only lasts a couple of seconds at a time. As you continue to obtain history, you find out that the baby was full term and there were no complications before, during, or after birth. He has been reaching all his developmental milestones up to this point. He is feeding appropriately and has been having regular wet diapers.

As you begin your physical assessment, you find that he is pink, warm, dry, and appears to be of normal size for a six-month-old. He interacts with you appropriately and is breathing normally. With help from mom, you’re able to get your monitor on and obtain the following vital signs. B/P 80/45, HR 132, RR 34, and O2 Sat of 100% on room air. Blood glucose is 82. Following the blood glucose test, you secure him on your cot and notice his eye roll back in his head as he flexes his arms and legs, lasting approximately 2 seconds. After a couple seconds he does the same thing a second and then a third time. Mom tells you this is what she was trying to describe, and she explains that it is happening more frequently and in clusters.

What are you going to do?

Infantile Spasms

Infantile spasms is a neurological seizure disorder that begins between the ages of 3 and 8 months, but can start any time before the child’s first birthday. Also known as West Syndrome, which was discovered in the 1840s, these spasms typically subside by the time the child is 4 or 5 years old. The spasms can be very subtle and could sometimes be confused with colic, normal reflexes, or the infant being fussy or irritable. This is because the infant could also cry during the event. However, you should notice that colic doesn’t occur in a series or cluster as the spasms do.

Infantile spasms are not common and only 2 to 4 in 10,000 births are diagnosed. It’s interesting because there are different causes, some of which could be changes in brain structure or how the brain has developed. They can also be caused by infection in the brain like meningitis or a hypoxic event during delivery. Most of the time genetic causes are associated with developing infantile spasms. Over 100 specific genes have been identified that may be responsible. It has also been discovered that there are larger portions of DNA that are either missing multiple genes (microdeletions) or contain extra genes (microduplications). However, what’s even more interesting to me is that infantile spasms can start for no reason at all with a healthy and typically developed child, also known as cryptogenic.

Here is a list of potential causes of infantile spasms:

Cerebral malformations

Perinatal brain injury or hypoxia

Cerebral infarctions or strokes

Tuberous sclerosis complex, a genetic condition causing benign brain tumors

Neurocutaneous syndromes, various genetic abnormalities causing brain malformations

Cortical dysplasia or abnormal brain development

Down Syndrome

Phenylketonuria (PKU), a metabolic disorder where the amino acid phenylalanine can’t break down.

Mitochondrial disorders

Zellweger syndrome, a rare genetic mutation that affects the formation of peroxisomes that assist in the breakdown of fatty acids

Nonketotic hyperglycinemia, mutations of genes which lead to a deficiency of the glycine cleavage enzyme complex, which normally breaks down glycine.

Diagnosis

Early diagnosis of infantile spasms is extremely important. This is because if they go unnoticed or undiagnosed, they can lead to other issues with the infant. Infantile spasms can lead to developmental regression and cognitive delays due to brain development being altered or slowed. This can also lead to the child developing epilepsy lasting their entire lives.

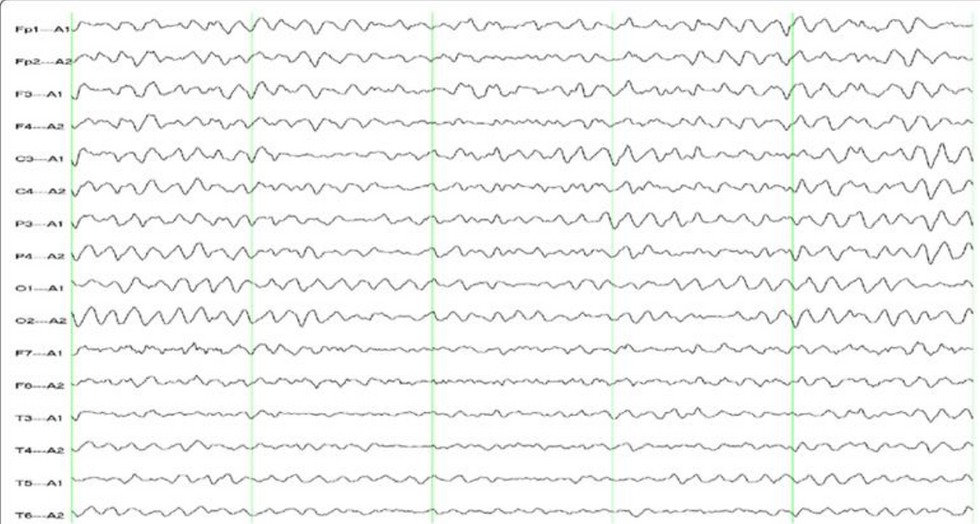

If it’s suspected that an infant is having spasms a video electroencephalography (EEG) is done. This is where 20 leads are placed on the infants’ head and brain waves are recorded while at the same time the video monitoring is watching for any motor seizure activity. If any spasm activity is seen, the EEG will be scrutinized to see if there were any changes to the infants’ brain waves during the same time frame. They will also look for other abnormal brain waves like hypsarrhythmia. This is when the brain waves appear chaotic with no organization along with high amplitudes. Visually, I like to think of these brain waves appearing similar to a very course ventricular fibrillation.

Figure 1. EEG with Hypsarrhythmia

Figure 2. Normal EEG

The video EEG can take multiple hours to complete up to a full day of observation. Once this is done, and depending on the results, additional testing will be done. An MRI will be conducted to look for structural malformations of the brain or if there are any other abnormalities like tumors or signs of ischemia. The infant will also be tested for the multiple genetic conditions that can manifest the spasms. This is important for the treatment phase.

Treatments

The first line therapy for infantile spasms is adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) or hormonal therapy, because they normally don’t respond to medications typically administered for seizure activity. This is an injection that is administered intramuscular daily at approximately the same time each day for several days up to several weeks. The medication is thought to work by increasing the levels of cortisol which lowers the amount of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH). This reduces the potential of excitability in the brain and lessens the likelihood of seizure activity. This medication continues to be studied and there is evidence to support long-term weekly injections versus daily if the infant is needing maintenance or prevention of relapse. This would have to be under the direct supervision of the neurologist and the benefits would have to outweigh the risks due to the medication weakening the immune system, making the child more susceptible to other illnesses.

An alternative to ACTH is oral Prednisone. Like ACTH, Prednisone is given over a period of several weeks and then tapered off. Dosing varies on what the neurologist orders and is administered every day divided into at least 2 doses. Prednisone’s mechanism of action also reduces the amount of corticotropin-releasing hormone and lowers the potential of seizure activity and excitability in the brain. It’s my understanding that Prednisone is used as an alternative to ACTH depending on what insurance will cover or if the cost isn’t feasible.

Another medication that can be considered is vigabatrin. Vigabatrin wasn’t approved by the FDA until 2009 due to the potential to cause retinal damage. For this reason, the benefits of the medication should outweigh the risk of vision loss if prescribed for infantile spasms. This medication can be supplied in a tablet or a powder form. The powder can be reconstituted with water to make an oral solution for administration for infants/children. Vigabatrin irreversibly inhibits the enzyme gamma-aminobutyric acid transaminase (GABA-T). By binding permanently to GABA-T, it prevents the breakdown of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA into succinic semialdehyde. This leads to elevated levels of GABA in the brain, which has been associated with a reduction in seizure activity. Dosing can vary but normally starts at 50mg/kg daily divided into two doses.

Another option for treatment is having the child start on a ketogenic diet. It has been found that a diet high in fat with lower carbohydrates and adequate amounts of protein can decrease spasm activity. It is thought that the ketones will cross the blood brain barrier, and the brain will utilize them in lieu of glucose. This results in increasing the activity of GABA and reducing glutamate. Additionally, they protect brain cells by lowering inflammation and oxidative stress, and they may influence genes and ion channels involved in controlling brain activity, decreasing the potential for spasm activity.

There can be many potential reasons for a child developing infantile spasms. Because of this, it is important to treat any underlying diagnosis or cause. In addition, there are potential surgical options including resection of the brain if the spasms are from a focal area. Another option that is not as invasive is performing an ablation if the source of the spasms are from a small focal area.

Case Conclusion

There isn’t a lot that we can do as EMS providers for the above patient. Hemodynamic monitoring and supportive care are key. If the patient hasn’t been diagnosed with infantile spasms and you see seizure activity, it would be reasonable to treat with benzodiazepines and or antiepileptics such as Dilantin or Keppra, if you carry them.

Infantile spasms are an emergency that requires early recognition and prompt treatment to improve outcomes. The severity and long-term effects can vary depending on the underlying cause and how quickly intervention begins. Delayed treatment increases the risk of permanent developmental delays or progression to other forms of epilepsy. While some children may experience ongoing challenges, early diagnosis and coordinated care can lead to significant improvements. We can play a critical role in identifying concerning seizure activity in infants and ensuring timely transport and communication with receiving facilities to support early intervention and better outcomes.

“The moral responsibility of the healer is to step inside the patients’ experiences and accompany them through the worst moments with empathy and expertise” -Dr. Paul Farmer

Resources

Brunson, K. L., Avishai-Eliner, S., & Baram, T. Z. (2002). ACTH treatment of infantile spasms: mechanisms of its effects in modulation of neuronal excitability. International Review of Neurobiology, 49, 185–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0074-7742(02)49013-7

Faulkner, M. A., & Tolman, J. A. (2011). Safety and Efficacy of Vigabatrin for the Treatment of Infantile Spasms. Journal of Central Nervous System Disease, 3, JCNSD.S6371. https://doi.org/10.4137/jcnsd.s6371

Hernandez, Angel and Wirrell, Elaine. “Infantile Spasms West Syndrome.” Epilepsy Foundation, 6 Jan. 2020, www.epilepsy.com/what-is-epilepsy/syndromes/infantile-spasms-west-syndrome.

Imdad, K., Abualait, T., Kanwal, A., AlGhannam, Z. T., Bashir, S., Farrukh, A., Khattak, S. H., Albaradie, R., & Bashir, S. (2022). The Metabolic Role of Ketogenic Diets in Treating Epilepsy. Nutrients, 14(23), 5074. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14235074

“Infantile Spasms - Child Neurology Foundation.” Child Neurology Foundation, 2020, www.childneurologyfoundation.org/disorder/infantile-spasms/.

Kato, T., & Ide, M. (2016). Long-term weekly adrenocorticotropic hormone therapy for relapsed infantile spasms. Journal of Rare Diseases Research & Treatment, 2(1). https://www.rarediseasesjournal.com/articles/longterm-weekly-adrenocorticotropic-hormone-therapy-for-relapsed-infantile-spasms.html

Philadelphia, The Children’s Hospital of. “Infantile Spasms Syndrome (West Syndrome).” Www.chop.edu, 16 Dec. 2020, www.chop.edu/conditions-diseases/infantile-spasms-syndrome-west-syndrome.

Puckett, Y., Gabbar, A., & Bokhari, A. A. (2023, July 19). Prednisone. National Library of Medicine; StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534809/

Ramantani, G., Bölsterli, B. K., Alber, M., Klepper, J., Korinthenberg, R., Gerhard Kurlemann, Tibussek, D., Wolff, M., & Schmitt, B. (2022). Treatment of Infantile Spasm Syndrome: Update from the Interdisciplinary Guideline Committee Coordinated by the German-Speaking Society of Neuropediatrics. 53(06), 389–401. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1909-2977

Ye, Y., Sun, D., Li, H., Zhong, J., Luo, R., Li, B., Zhu, D., Li, D., Huang, S., Jiang, Y., Xiao, N., Chen, Y., Zhang, Y., Yu, M., Shen, X., Gao, L., Zheng, G., Zhao, C., Yuan, B., & Liao, J. (2022). Correction to: A multicenter retrospective cohort study of ketogenic diet therapy in 481 children with infantile spasms. Acta Epileptologica, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42494-022-00081-5

Zimlich, Rachael. “What Is Hypsarrhythmia on an EEG?” Healthline, 22 June 2023, www.healthline.com/health/hypsarrhythmia-eeg.